History of the Murals

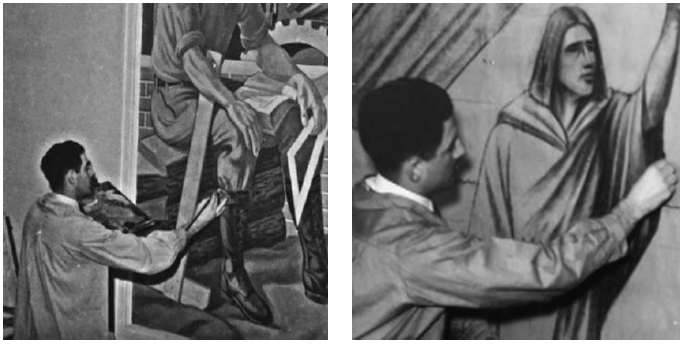

During the Great Depression, the United States Federal Art Project, (1935-43) part of the larger Works Progress Administration provided employment to thousands of artists. Minnesota’s John Martin Socha, being paid a “plumbers wage”, was commissioned to paint several murals in Minnesota including those in the Kiehle auditorium of what was then called the Northwest School of Agriculture (NWSA). The murals were installed in 1942.

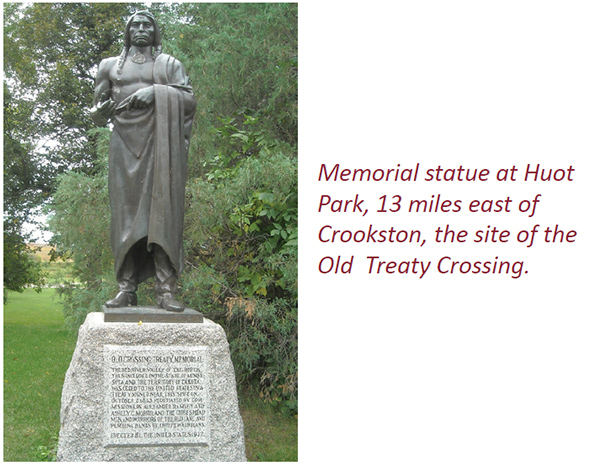

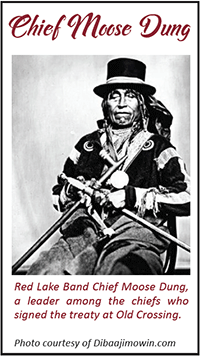

The NWSA Class of 1932, who donated funds for the art materials, presented the murals to the school at the annual Parent’s Day program held on Saturday, November 7, 1942. Northwest School Superintendent T.M. McCall formally accepted the murals on behalf of the campus and in his remarks recognized the historical significance of the art. Attending the ceremony that day were Mrs. C.A. Smith of Grygla, Minnesota and her daughter Myrtle a student at the school. Mrs. Smith was the granddaughter of Chief Little Boy, a signer of the Old Crossing Treaty.

Murals, or paintings on walls, present images that tell stories. As works of art that are largely made for public viewing, murals often present versions of histories, expressions of identities, and sources of inspiration. Proposals for art commissioned by The Federal Arts Project had to be submitted for approval and were to reflect the theme of a “useable past” to stir the American economy and spirit during a time of large unemployment and financial uncertainty. Many of these murals were intentionally made to present a version of American history that emphasized productivity and economic strength to encourage citizens during harsh times.

John Martin Socha was trained by one of the most influential muralists in history, Mexican artist Diego Rivera. Like Rivera, Socha created works of art that depicted the achievements, fortitude, and industriousness of working people and the presence of indigenous people in the history of the nation-state. Employed by the federal government, Socha drew upon American mythologies and notions of Manifest Destiny to present the development of the Nation as one that was rooted in exploration, discovery, willpower, and strength to inspire others. In doing so, the effects of Manifest Destiny for Native people, who suffered immensely from these ideas and actions, became secondary and nearly absent in this work of art. Absent too, is the presence of women and children and Latinx migrant workers who contributed greatly to the development of the land.

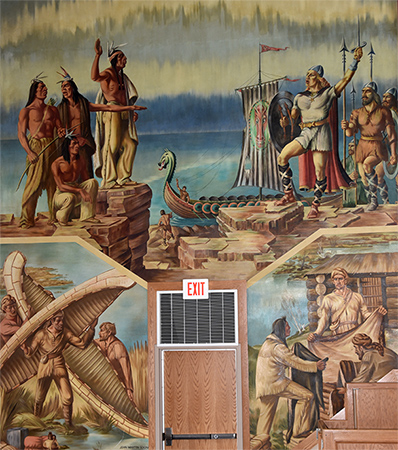

Following notions of a linear and singular timeline of economic and cultural progress and development, this mural reads left to right, from past to present. Both sides of the mural contain a large monumental painting at the upper half of the wall depicting a historical event, and two smaller, more intimate paintings of economic activity and trade at the bottom. In the large painting to the left of the stage, Socha creates a depiction of the origins of American history with the arrival of Vikings to North America, encountering Native people on the shores, and perhaps Minnesota shores. The decision by Socha to depict Vikings rather than Christopher Columbus as the first Europeans to arrive in North America was quite revolutionary during his time. As a resident of Minnesota with a large population of Scandinavian immigrants, Socha may have recognized the power of claiming this legacy of deep historical roots in the region for modern-day Scandinavian descendants residing in the area. Rising to the top of the cliffs after docking a large dragon-headed long ship that helped navigate their way to this newly chartered land, Viking arms are raised in victory and strength upon their arrival. They carry swords and shields with sculpted bodies in the image and clothing of Greek gods rather than Nordic warriors. On the left side of this painting Native men, adorned in muted colored hides, red-skinned and bare-chested, greet the newcomers with a hand raised, the signature gesture non-Native artists typically use to depict Native greetings and welcome.

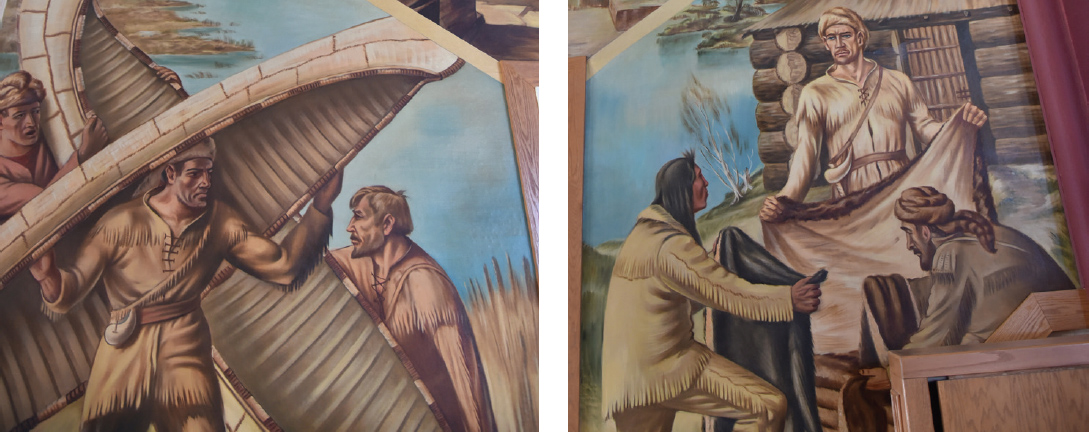

Below this epic historical rendering are two smaller paintings that depict the emergence of a newly-established global economy. On the left, French fur-traders and voyageurs, tired and carrying their heavy canoes, portage waterways for trade in the 17th century. On the right early 19th century European- American homesteading appears; a log cabin grounds the painting, referencing the shift from economic mobility to settlement. The settler stands tall, while both the Native man and French trader wearing a signature pelted-hat remain at a lower, and less powerful position.

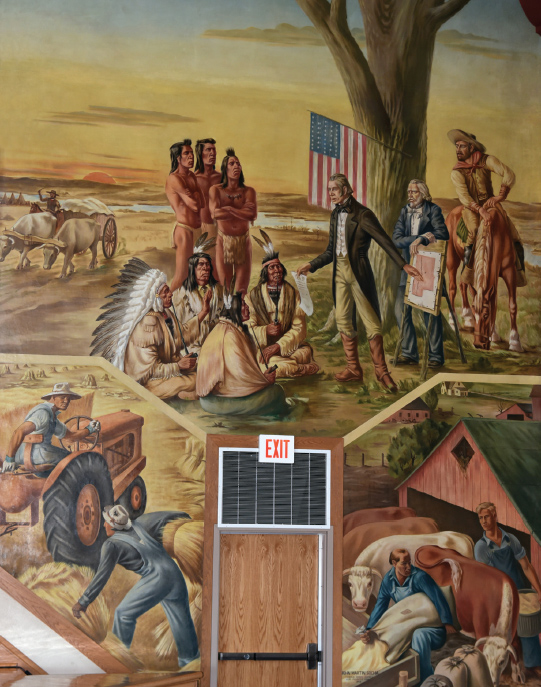

The large painting to the right of the stage depicts a new era that seems to read as a moment of inevitability and Manifest Destiny. To the left, incursion into the region by oxcart trade as the sun sets on an apparently earlier time that has now disappeared into history. In the central field, Socha allows the viewer to be a witness to a critical moment in Minnesota history; the cessation of lands of Native peoples with the US government. An American flag staked to a tree, a treaty dangling in front of a Native council, and a map of land in the background signal governmental negotiations and control. An official diplomat, wearing a tailored long coat, stands while a Native council remains appropriately seated in discussion, smoking pipes. Pipes, like the open-faced hand gesture, serves as generic Native greeting and agreement to this cessation.

However, unlike many artists of his era, Socha also paints a more complicated picture of this important event. At the left of the painting, young warriors stand near a Native council sitting, and appear with folded arms with skepticism and mistrust, revealing the real diversity of opinions held by Native people about these negotiations with the federal government. Likewise, standing behind the governmental official, two other European-American men appear, eavesdropping on these negotiations. The man in a blue suit, perhaps a wealthy landowner, and a cowboy on horseback, listen intently, as their own interests are also invested in these negotiations. They peer menacingly, representing clear ties between governmental negotiations with settler benefits.

As modern viewers of the murals, it is important to note the dark context that lead to the October 2, 1863 signing of the Treaty of Old Crossing. Alexander Ramsey, the second Governor of the state of Minnesota, had ordered multiple "punitive" strikes by Minnesota militia against Dakota settlements following the Dakota Conflict of 1862. Ramsey stated, "Our course is plain--the Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state." On December 26, 1862, federal officials hung 38 members of the Dakota tribe in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Then, in early 1863, Minnesota's third Governor, Henry A. Swift, issued multiple executive orders authorizing bounties for Indian scalps.

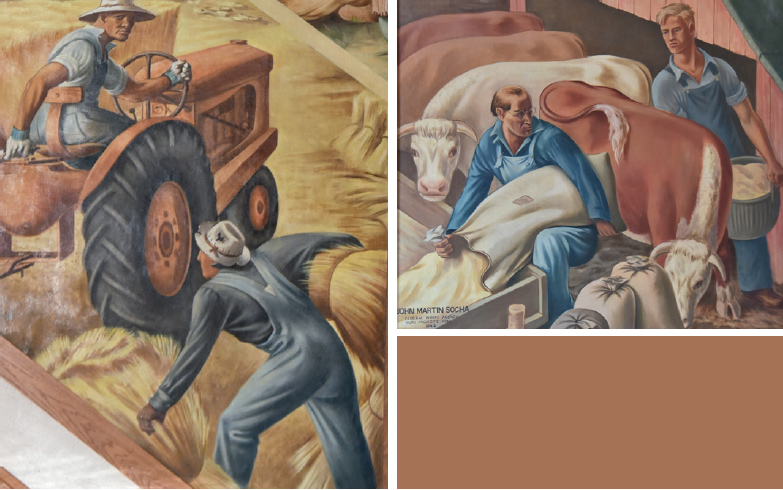

At the bottom part of the panel, two smaller scenes appear. On the left a farmer on a tractor tills the land and wheat shocks appear in the background representing cultivation and the vast land and agrarian settlement and productivity. Orange tractors and blue clothes indicate these farmers embody progress, technology and industrialization. The right panel is filled with activity, productivity, and surplus, with domestic cattle and troughs, farmers feeding their livestock, grain bags overflowing, and barns and houses in the background. This is the finale of the mural and indicates the progression of American history as beginning with European exploration, 18th century fur trade, 19th century settlement, and a productive and settled agrarian society, a nostalgic history that can inspire Euro-Americans during hard economic times but with no Native Americans visible in the present day.

There are techniques and styles artists employ to signify larger ideas, depict emotions, and affirm identities. In this mural, the depiction of Native people follows a particular pattern that illustrates differences and false ideas of primitivity. Native people’s skin tones are red, and more deeply red when they are depicted without much clothing. Facial and body features are exaggerated. These features appear almost in comic-like fashion, with overly sculpted, chiseled cheekbones, long noses, and wide pursed lips. Clothing, if worn, is tan and natural toned indicating more primitivity. Yet the majority of Native people embraced the variety of materials available in global trade by the 1600s, favoring exotic goods and materials of all colors and varieties. By contrast, Europeans and Euro-Americans’ creamy complexions, smooth facial features and elaborate and colorful dress indicate more cosmopolitan tastes.

Socha presented the beginnings of North American history with the arrival of Vikings. For millennia, Native North American people have created large metropolitan centers with massive populations, complex and sophisticated trade networks linking South America to North America, stewarded and cultivated lands and crops, and developed extraordinary technologies in irrigation, ecological knowledge, astronomical knowledge, etc. While Native people appear in the first four paintings of the mural, they disappear after the treaty is signed. Vikings appear, fur traders appear, settlers appear, industrialization and new agricultural technologies appear, farming and livestock appear, but Native people disappear. Native people never disappeared, nor did their impact on regional and national economies and the identity of the United States.

About the Artist

John Martin Socha (pronounced So-sha), (1913-83) was a native Minnesotan and graduate of the University of Minnesota. He taught at Marshall High school in Minneapolis. Socha also studied at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and with renowned Mexican artist Diego Rivera.

Other Socha murals and his numerous other works are displayed throughout the Midwest and have been exhibited throughout the United States and Mexico. Several of Socha’s works are on display in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Learning from the Murals

While we wish to acknowledge the richness and significance of the Socha murals, we also recognize the narrow view of history they present, one that excludes the contributions of the great diversity of people who have lived here and that ignores the wrongdoing often imposed upon them. We seek to continually use the murals to shed light on lessons we can learn from them to help build a bridge to a better understanding of others and ourselves.