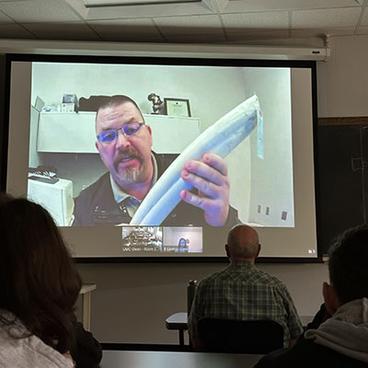

It’s not every day you get to listen to a University of Minnesota Crookston alum talk about the illegal importing and exporting of elephant tusks and rhino horns, but Natural Resources students recently had that chance thanks to Associate Professor Phil Baird. Alumnus Chad Hornbaker 2001, who works for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska, was a guest presenter over Zoom and shared what it’s like to be a wildlife inspector and K-9 handler in the office of law enforcement in Anchorage.

Wildlife Inspector Hornbaker and his newly retired K-9, Dock, worked at ports of entry within Alaska and the Ted Stevens International Airport detecting wildlife and invasive species. A typical day was spent with Dock using his nose to inspect packages in parcel facilities and/or on cargo planes. If a package was found to contain wildlife, inspectors would investigate whether the wildlife in question required a permit, was legal and allowed to be shipped, or was unlawfully imported/exported and needed to be confiscated.

Holding up a chunk of elephant tusk to show the students, Hornbaker told them an exporter stained it with tea to make it appear as if it was an antique to smuggle illegal ivory.

“We have the Endangered Species Act that regulates the ivory trade, and in the recent past, auction houses and shops were importing stained ivory to sell, and importing under permits they falsely stated the ivory was obtained prior to when elephants were listed as protected under ESA,” he explained.

Hornbaker also showed the audience walrus ivory, describing how to identify the difference when compared to elephant or mammoth, plus a four-and-a-half pound horn from a black rhino which can bring upwards of approximately $50,000 a pound in the illegal trade.

“Rhino horn is said to have medicinal traits and I had heard people would grind and snort it at clubs, or put it in their drink so they wouldn’t get a hangover,” Hornbaker admitted. “I was given this horn for training with my K-9 from a rhino that had passed at a zoo. Having this real rhino horn allows us to train our K-9 partners to be able to detect and interdict illegal rhino horn in the wildlife trade.”

Showing a sea turtle shell, Hornbaker said many people don’t realize sea turtles are endangered and will arrive at U.S. airports from traveling abroad with a sea turtle head belt buckle, sea turtle shell jewelry, or a fully mounted sea turtle to hang on their wall at home. He mentioned he’s been asked by individuals what the “big deal” was if the animal was already dead and for sale in another country, and Hornbaker responded, “Once the purchase is made the person selling the wildlife now has to go out and take more protected wildlife to supply the demand.”

“We see a lot of reptiles in the trade such as a python skin handbag, which pythons are not endangered but they are regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and the importer needs a permit issued from the country of export,” he continued. “Currently we are dealing with many United States native turtle species, which are regulated by CITES, being unlawfully harvested, and smuggled from the United States. An ornate eastern box turtle can bring upwards of $20,000 U.S. in foreign countries as a pet. The brighter the color, the more they’re worth.”

Hornbaker says one individual who was arrested for smuggling U.S. turtle species through the mail to foreign countries made over $2 million U.S. The person allegedly hired college students to collect turtles to be shipped unlawfully from the United States and was sentenced to three years in prison, which Hornbaker said is not typical for wildlife crime.

“There are tens of thousands of packages coming through ports in the U.S. and our K-9s are trained to detect the wildlife items I’ve shown today,” Hornbaker pointed out.

When asked by a student how long it took to train Dock, Hornbaker joked that it took longer to train himself.

“It’s a 13-week training program and we currently have six K-9 teams in the wildlife inspection program,” he described. “The handler is trained to recognize the K-9’s change of behaviors and primary care of the K-9. If the K-9 detects wildlife, they will alert the handler by sitting if it’s a stationary object like a vehicle or pallet of cargo, or by pawing the object if the K-9 is on a moving belt.”

“You have to be a seasoned wildlife inspector to apply as they want you to know the wildlife inspection program well before taking on a K-9,” Hornbaker added, making note that now Dock is officially retired the K-9 gets to go home with Hornbaker after an adoption agreement with the USDA was confirmed. “I have heard that 50 percent of federal employees are eligible to retire in the next five years, so you (students) are coming out of school at a good time if you want to get a federal job.”

Hornbaker recalled the path he took to get from Customs and Border Protection in Pembina, N.D., to becoming a wildlife inspector with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“I applied for jobs after graduating in December 2001 and, after 9/11, Customs was mass hiring so I applied for Customs while I was applying for other jobs,” he explained. “After working for Customs for four years, I applied for wildlife inspector at Pembina. I left on a Saturday wearing a Customs uniform and came in Monday wearing a wildlife inspector uniform.”

Hornbaker’s words of advice for students interested in natural resources or other government-related jobs was to network, contact agencies and show up in person, and volunteer as it offers the “same weight” on a federal application as paid work.

Written for the December 2023 Torchlight e-Newsletter